Little known creative endeavors might spur your own creative juices.If not for the Society of Jesus, we would not be enjoying some basics taken for granted in the modern world. Nerdy academic Jesuits and their swashbuckling, globe-trotting missionary brothers have made significant contributions not only in astronomy, seismology, mathematics and technology, but also in theatre, botany, medicine and international cuisine.

- The Calender

Christopher Clavius, S.J. (1538–1612), was a renowned German mathematician and astronomer who modified Aloysius Lilius’ initial proposal for the Gregorian Calendar, the internationally-accepted civil calendar we use today, which was promulgated in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII.

Italian Fr. Roberto Busa, S.J. (1913–2011) was the pioneer in computational linguistics who, while studying Aquinas’ writings, convinced IBM founder Thomas J. Watson that computers could be used for text, not just numbers. Read more about Busa, here.

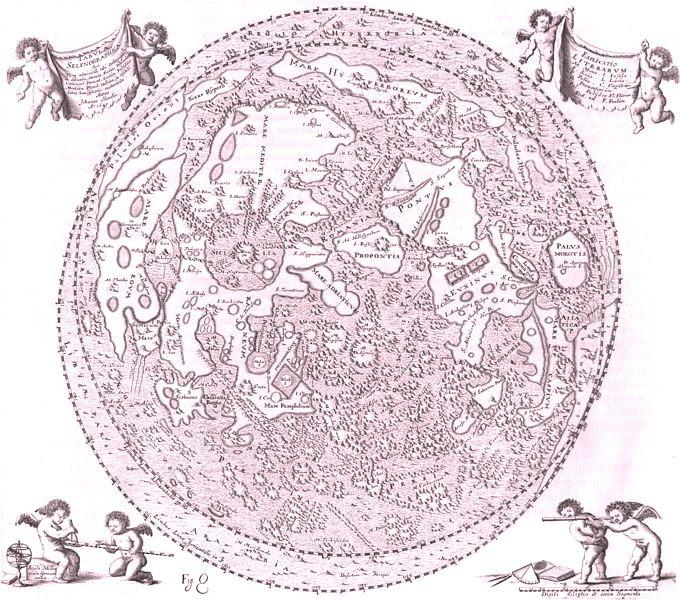

- Modern Selenographs

The Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli, S.J. (1598–1671) and mathematician and physicist Francesco Maria Grimaldi, S.J. (1618–1663) published a selenograph in Almagestum Novum (1651), mapping the craters, mountains, and other features of the moon; this formed the basis for modern lunar nomenclature.

Jean Charles de La Faille, S.J. (1597–1652) was a Flemish mathematician; in his book Theoremata de centro gravitatis partium circuli et ellipsis (1632) he determined the center of gravity of the sector of a circle.

André Tacquet, S.J. (1612–1660) was another Flemish mathematician, whose work prepared the ground for the eventual discovery of the calculus.

- The Trap Door

Jesuits wrote and directed plays in their 16th- and 17th-century schools, and a 17th-century Jesuit teacher is held to have invented the trap door. Jesuits are also credited with perfecting the sheer curtains used in theaters, known as the scrim.

When Portuguese Jesuit missionaries arrived in Japan in the 16th century, they began to deep-fry shrimp while abstaining from meat on Ember Days, an ancient Catholic observance corresponding with the four seasons. “Tempura” and “ember” both come from the Latin term, Quatour Tempora, “the four seasons.” In a twist of poetic justice (or divine retribution?), Tokugawa Ieyasu, the shogun who started the persecution of Catholics, died from over-eating tempura.

- Jesuit Tea (yerba maté)

In the mid-17th century, Jesuits domesticated the maté plant in South America, producing a beverage known as “the elixir of the Jesuits,” or Jesuit tea (Spanish té de los Jesuitas; German Jesuitentee). They were probably trying to save the native population from the scourge of alcoholism. For many years, this strong herbal tea was banned; to consume it bore the penalty of excommunication.

- Passionfruit/Passionflower

Spanish Jesuit missionaries named the passionflower, or “flower of the five wounds,” after Christ’s Passion.

* The pointed tips of the leaves were taken to represent the Holy Lance.

* The tendrils represent the whips used in the flagellation of Christ.

* The ten petals and sepals represent the ten faithful apostles (less St. Peter the denier and Judas Iscariot the betrayer).

* The flower’s radial filaments, which can number more than a hundred and vary from flower to flower, represent the crown of thorns.

* The chalice-shaped ovary with its receptacle represents a hammer or the Holy Grail

* The 3 stigmata represent the 3 nails and the 5 anthers below them the 5 wounds (four by the nails and one by the lance).

* The blue and white colors of many species’ flowers represent Heaven and Purity.

The flower has been given names related to this symbolism throughout Europe since that time. In Spain, it is known as espina de Cristo (“Christ’s thorn”). German names include Christus-Krone (“Christ’s crown”), Christus-Strauss (“Christ’s bouquet”), Dorn-Krone (“crown of thorns”), Jesus-Leiden (“Jesus’ Passion”), Marter (“Passion”) or Muttergottes-Stern (“Mother of God’s star”).

9. Camellias and the St. Ignatius Bean

Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who devised our modern system of naming organisms, named camellia flowers after a Jesuit brother, Georg Josef Kamel S.J. (1661–1706). Kamel spent his life documenting plants and animals in the Philippines as part of his medical and pharmaceutical practice. He discovered the healing properties of the St. Ignatius Bean (Strychnos ignatii), a source of strychnine today. Linnaeus was so impressed by Brother Kamel’s work that he changed the name of the genus Thea to Camellia. This genus includes the shrubs from which we derive tea.

- Quinine (Jesuit’s Bark)

Seventeenth-century Spanish Jesuit missionaries in Peru learned from the natives that cinchona bark could cure malaria. Jesuits took the remedy throughout the world, curing the emperor of Japan. Today, it is also used in tonic water, so thanks to the Jesuits, we have gin and tonic.

- The Megaphone

Athanasius Kircher, S.J. (1602–1680) was a German Renaissance scholar and polymath who was one of the first people to observe microbes through a microscope, and theorized that the bubonic plague was spread by infectious microorganisms. While not busy descending into volcanoes, surviving shipwrecks and beating the plague, Kircher invented clocks, robots and the first megaphone.

- The Umbrella

Parasols and umbrellas were introduced to France and England in the 17th-century by Jesuits who had visited East Asia. On 22 June 1664, the English writer John Evelyn mentioned in his diary a collection of Father Thompson S.J., who had been in China and Japan. Among the artifacts were “fans like those our ladies use, but much larger, and with long handles, strangely carved and filled with Chinese characters” – parasols.

So, the next time you put your feet up under a beach umbrella while sipping a gin and tonic, munching on tempura and passionfruit, and surfing the internet, remember Saint Ignatius and his Society of Jesus, who have greatly added to our knowledge, our pleasures and our comforts — Ad maiorem Dei gloriam, all for the greater glory of God.