For some, Chesterton is best taken in small bites and excerpts.I suppose it will be considered heresy in some quarters, but I’ve never been what you would call a fan of the writing of G.K. Chesterton. Some people can’t get enough of GKC. I can.

Not that I haven’t tried to read him. Now and then, failing to acquire this particular taste and suspecting the fault lies with me, I’ve tackled still another book by Chesterton in hopes of falling in love with him as others have done.

In this way I’ve consumed quite a bit of Chestertonian prose. I’ve read The Everlasting Man and The Man Who Was Thursday, I’ve read the books about St. Francis of Assisi and St. Thomas Aquinas, I’ve read a smattering of Father Brown stories and a few essays. And I’ve always had the same question at the end: What’s all the shouting about?

Chesterton the man, as he comes through in his writing, was obviously an admirable fellow—intelligent, good humored and generous even toward those with whom he disagreed. (Even in the “death of God” man, the raging German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, he sees something to speak well of, calling him “brave, proud and pathetic.”)

But Chesterton the writer I find, not to put too fine a point on it, more or less impenetrable. Amid the verbal cleverness and rhetorical flourishes it can be difficult—for me at least—to tell what he’s saying. “Give me a break, Mr. Chesterton,” I silently plead. “Keep it short and simple.” He seldom does.

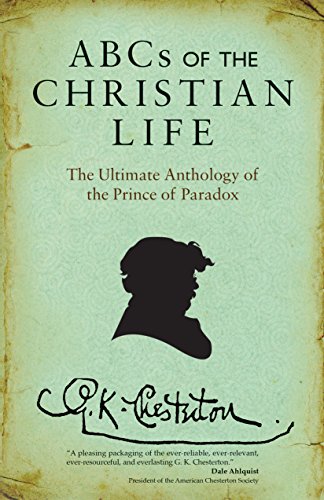

That said, I’m delighted to report that I’ve finally read a Chesterton book that goes a long way toward making him accessible even to me. The title is ABCs of the Christian Life, and it’s a collection of excerpts, ranging from several paragraphs to several pages, drawn from Chesterton books and essays, and arranged alphabetically according to subject, from “Asceticism” to “Zion.”

My thanks to the anonymous editor or editors who assembled this material in a compact volume of 180 pages for Ave Maria Press. As an introduction to Chesterton for people who haven’t read him, or a kind of synthesis for those who have and find him hard going, the book is a big help.

Encountering Chesterton in short takes is the key to it. Consider a throw-away line in a graceful tribute to Queen Victoria. Of William Gladstone, the British Liberal leader who served four times as prime minister, Chesterton writes:

“Mr. Gladstone seemed a fixed and stationary object … for the same reason that one railway train looks stationary from another; because he and the age of progress were both travelling at the same impetuous rate of speed. In the end, indeed, it was probably the age that dropped behind.”

Chesterton, a convert to Catholicism, was an ardent defender of the faith who practiced apologetics with a kind of good-natured ferocity. Writing in a pre-ecumenical era (he died in 1936), he calls Protestants “Catholics gone wrong” but displays no ill-will or rancor toward them. Truth matters to Chesterton, matters immensely, and truth may never be sacrificed to expediency. His own credo is visible in an excerpt from his book Heretics:

“There is one thing that is infinitely more absurd and unpractical than burning a man for his philosophy. This is the habit of saying that his philosophy does not matter, and this is done universally in the twentieth century.”

At his best, I’m obliged to admit, GKC was indeed very good. You will find quite a bit of his best in this small volume.