The Passion of Christ, including his suffering, crucifixion, and death, is a central tenet of Christian theology and soteriology – and the main subject of most iconographic depictions of Christ. Throughout the whole history of Christianity, artists drew on a rich vocabulary of symbolism to visually represent the events and theological significance of the Passion – but especially during the Middle Ages, when Christian philosophy and theology developed aesthetic paradigms that would shape the visual culture of Europe, the Mediterranean, and beyond.

While symbols such as the cross, the Nazarene, and the deceased Christ are somewhat widely recognized, other lesser-known motifs offer unique perspectives on Christ’s sacrifice. Here’s three of them.

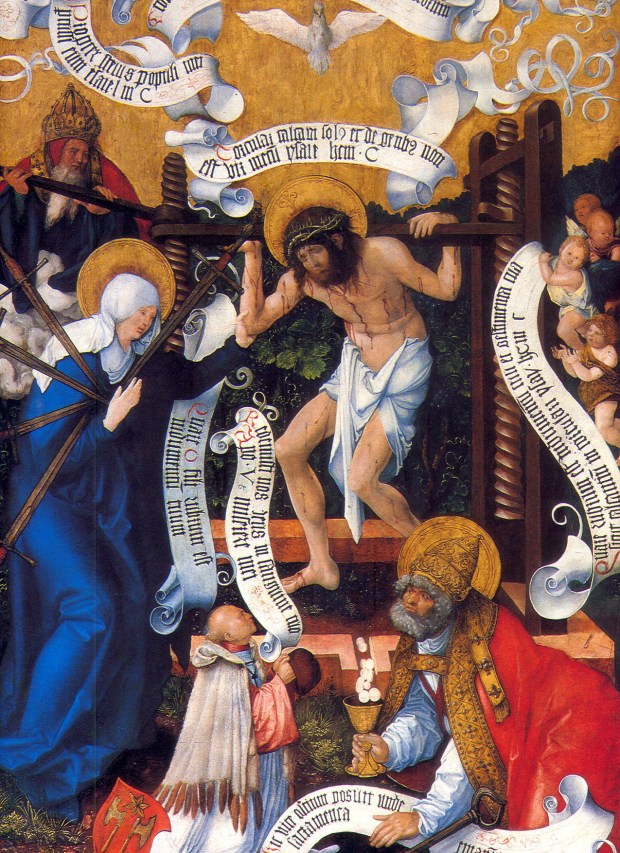

1. The Mystical Winepress:

The image of the mystical winepress presents a moving and multifaceted analogy. In this design, Christ is depicted as if in a wine press, standing over the grapes. As the press is turned, he is burdened with the weight of the main log, drawing a parallel between the wine flowing from the press and the blood leaving his body –that is, it is a clearly Eucharistic image. This image underscores the connection between Christ’s Passion and the Mass. In addition, the wine press evokes Old Testament references, particularly Isaiah 63:2, where God treads the grapes of his wrath, signifying judgment against his enemies. By symbolically embodying the grapes, Christ himself becomes the sacrifice that transforms the wrath of God into the redemptive wine of salvation.

2. Arma Christi:

The Arma Christi, Latin for “Christ’s weapons,” refers to the instruments associated with the Passion. These objects, including the nails, lance, hammer, and sponge, became powerful symbols in their own right, even if depicted separately. Often represented without Christ, these objects served as stark reminders of the Passion, inviting contemplation and devotion. The arrangement of these objects can be somewhat free, as it is not attached to a particular iconographic setting. For example, the nails could be displayed in the shape of a cross – as if further reinforcing their connection to the central symbol of the Passion.

3. Christ as a Pelican:

In medieval bestiaries (collections of animal lore), the pelican was often imbued with Christological symbolism. According to ancient Greek legends, a mother pelican would pierce her own breast to feed her young with her blood. This sacrificial act was seen as a parallel to Christ shedding his blood for the salvation of mankind. Although less common than other Passion motifs, the image of Christ as a pelican offers a tender portrayal of his self-giving love, emphasizing the depth of his compassion and the intimate connection he establishes with his followers.

These three motifs, while perhaps less familiar today, played an important role in medieval Christian visual culture – both early and late. They served not only as artistic representations of the Passion, but also as powerful tools for meditation, prayer, and theological and moral reflection.

By rediscovering and understanding these lesser-known symbols, we can deepen our appreciation of the many ways in which Christians once sought to understand and express the profound mystery of Christ’s redemptive sacrifice.