It's hard to imagine a time when the world knew Notre-Dame de Paris without a spire. The cathedral's medieval spire was dismantled in 1786 due to its dangerous state of decrepitude, and disappeared from the Parisian landscape for over half a century.

A few photographs bear witness to this distant era. The most attentive observers will notice that the statues in the “gallery of the kings” on the façade had also disappeared following the French Revolution, and that the gargoyles and grotesques, invented by Viollet-le-Duc, had not yet taken their place on the upper galleries.

In the first half of the 19th century, Notre-Dame de Paris was in a critical state. The restoration work appeared colossal, and the Paris authorities even considered destroying the building.

Fortunately, popular enthusiasm for this precious example of medieval architecture saved Notre-Dame from destruction. With the advent of photography, the cathedral was immortalized from every angle. These pictures are precious testimonies that allow us to appreciate the state of Notre-Dame before and during Viollet-le-Duc's restoration project (1844-1864), as well as the liturgical arrangements of the time.

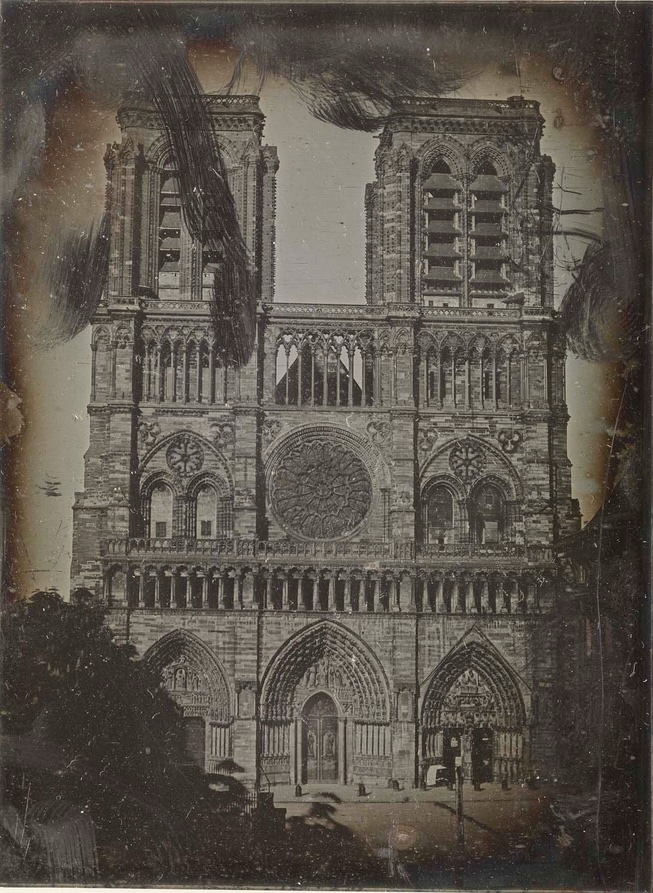

The earliest extant photo of Notre-Dame?

This daguerreotype of Notre-Dame de Paris dates from 1838 and was taken by Louis Daguerre himself, who had started developing the technology together with Nicéphore Niépce about 10 years earlier. The process had not yet been made publicly available when this photograph was taken.

Notre-Dame’s main façade in 1843

This photo, taken before Viollet-le-Duc's major restoration work began in 1843, shows Notre-Dame as we know it today. In 1771, architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot removed the medieval trumeau (central column) from the Last Judgment doors and part of the lintel to facilitate the passage of the canopy during processions. A wooden arcade evoking Mary fills the void. The doors have also been replaced, depicting Christ carrying his cross and Mary weeping with grief at the death of her son. Also noticeable above the doors is the empty “gallery of kings.” All the sculptures were destroyed during the French Revolution and never replaced until Viollet-le-Duc's restoration.

The state of the flying buttresses before restoration of Viollet-le-Duc, 1851

In the first half of the 19th century, Notre-Dame de Paris was in such a state of decay following numerous demolitions and ransackings that the Parisian authorities considered its outright destruction. Fortunately, popular enthusiasm and the release of Victor Hugo's novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame, published in 1831 — which enjoyed immediate success — stopped the madness of the demolition.

In 1851, photographer Henri Le Secq immortalized the flying buttresses of the cathedral. Several stones were fallen, testifying to the catastrophic state of Notre-Dame.

Notre-Dame de Paris early in its restoration, 1852

This photo, taken around 1852 by Edouard Baldus, gives a good overview of the state of the cathedral and the surrounding developments. Houses, which no longer exist, stood next to each other on the south façade.

Notre-Dame de Paris under restoration, before 1853

Taken in 1853, this photograph by Charles Nègre shows the changes to Notre-Dame de Paris following the first restorations of Viollet-le-Duc. The gallery of kings in the western façade now has its 28 kings of Judah, reconstructed thanks to the workshop of Geoffroi-Dechaume.

At the central portal, craftsmen are working on restoring the door in order to restore the original lintel and trumeau, as evidenced by the large scaffolding that covers the entrance. At the level of the upper galleries, we notice the gargoyles and grotesques added by Viollet-le-Duc, which did not exist in medieval times. Finally, the large neo-Gothic spire designed by Viollet-le-Duc to replace that of the 13th century which had been dismantled, still does not exist at this time.

The rose window is notably without stained glass.

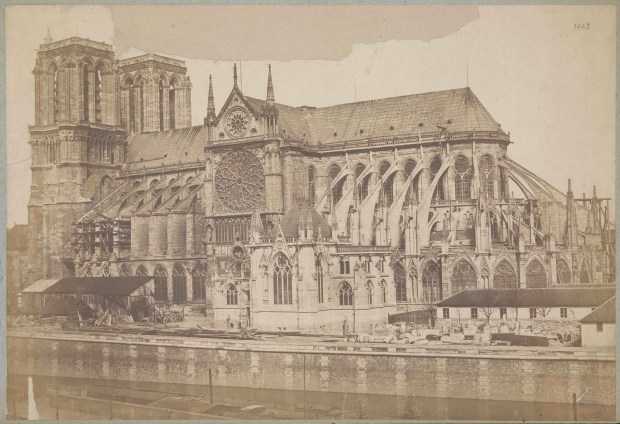

Scaffolding on the apse of Notre-Dame, 1853

In 1853, work was progressing well on the apse of Notre-Dame, which had been partly covered by scaffolding.

Notre-Dame de Paris decorated for the baptism of the Imperial Prince, 1856

Three years later, the facade of Notre-Dame de Paris was decorated on the occasion of the baptism of the imperial prince, Eugène Louis Jean Joseph Napoléon, the long-awaited son of Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie. The main door has been fully restored and the rose window has its stained glass.

The construction of the spire, 1857

In October 1857, Viollet-le-Duc received approval for the construction of a new spire. He commissioned a carpenter to rebuild it to replace the old one, which had been dismantled between 1786 and 1792. This new spire would stand until the fire of 2019 destroyed it completely.

Notre-Dame with the restored spire (undated)

In this photo, the renovations have obviously advanced significantly with the addition of the new spire. In the foreground, the hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu, is being rebuilt. This dates the photo to between 1867 and 1878.

The new spire of Notre-Dame de Paris, 1892

Taken in 1892 by Médéric Mieuxement, this photo shows the restored spire, which is very different from the previous design. The old one was a bell tower that housed five bells. The new one, designed in a neo-Gothic style, is made up of 500 tons of wood and 250 tons of lead, and culminates 315 m above the ground.

The interior of Notre-Dame de Paris, 2nd half of the 19th century

Let's go inside the cathedral. In the second half of the 19th century, the layout was very different from what we know today. We find the large chandeliers made by Viollet-le-Duc but formerly placed in front of the pillars, whereas today they are placed between. In the background, we can see the choir, access to which is limited by a wrought iron barrier that no longer exists today.

The statue of the Virgin Mary, 2nd half of the 19th century

The famous statue of the Virgin Mary, sculpted in the 16th century, formerly belonged to the Saint-Aignan chapel of the Cloître Notre-Dame. Placed on the trumeau of the Virgin's portal in 1815, it remained there until 1855. On that date, Viollet-le-Duc moved it inside the cathedral where it has remained ever since. In the 19th century, a large canopy and a small barrier surrounded it to protect it.